The Super Bowl has evolved from a simple championship determination contest into the single most valuable event property in the United States, serving as a convergence point for sports, corporate marketing, and global media. This evolution has necessitated a rigorous transformation in the criteria for host site selection, shifting from a model of rotation based on fairness or novelty to a model of extraction based on economic capacity, risk mitigation, and luxury infrastructure.

As the National Football League solidifies its hosting requirements, specifically the “Infrastructure Trinity” of climate control, seating capacity, and hotel inventory, a distinct class of venues has emerged: the permanently excluded. These are the iconic American stadiums that have never hosted a Super Bowl and, absent billions in renovations or complete demolition, never will.

The Infrastructure Trinity: Climate, Capacity, and Logistics

To understand why venues as historic as Lambeau Field or as dominant as Arrowhead Stadium are barred from the Super Bowl, one must first dissect the operational manual that governs the event. The NFL evaluates potential hosts based on a triad of non-negotiable pillars.

- The first is the climate mandate. The league requires that a host city have an average daily temperature of at least 50 degrees Fahrenheit on the game date, or a climate-controlled stadium featuring a roof. This requirement serves two purposes: protecting the passing game from high winds and extreme cold that increase variance, and ensuring the comfort of the corporate class. The week leading up to the Super Bowl is filled with outdoor concerts and VIP activations that demand a temperate environment, prioritizing the comfort of sponsors over the gritty “football weather” that fans often romanticize.

- The second pillar is capacity. Historically, the NFL has mandated a minimum seating capacity of 70,000 for Super Bowl venues to maximize ticket revenue, which is shared among all 32 franchise owners. Every seat below this threshold represents a direct loss in shared revenue. In recent years, while the raw seat count has become slightly less critical than the yield per seat, venues with capacities below 65,000 are viewed as mathematically inefficient unless they possess an overwhelming density of luxury suites.

- The third pillar, often the invisible barrier for smaller markets, is connectivity and hotel inventory. The NFL requires access to hotel rooms equaling roughly 35 percent of the stadium’s total capacity within a one-hour drive, a logistical necessity for housing the influx of media, staff, and partners that descends upon the host city.

The Logistical Impossibility of Lambeau Field

Lambeau Field in Green Bay, Wisconsin, stands as the most prominent victim of these criteria. While it is the spiritual center of the league and the longest-continuously occupied stadium, its location renders it functionally ineligible. The primary disqualifier is not merely the average February high temperature of 27 degrees Fahrenheit, but the severe lack of hotel infrastructure. The Greater Green Bay area possesses a hotel inventory of approximately 4,000 to 5,000 rooms, a fraction of the NFL’s 25,000-room requirement. To host the event, organizers would be forced to utilize lodging in Milwaukee and Madison, located nearly two hours away.

In the context of a Wisconsin winter, this creates a transport failure mode where a single ice storm on Interstate 43 could sever the connection between the lodging hubs and the stadium, stranding thousands of fans and VIPs. Mark Murphy, the outgoing President of the Packers, has publicly conceded the issue, stating that the organization accepts they will not host a Super Bowl, settling instead for the 2025 NFL Draft which occurs in milder April weather. The draft serves as a consolation prize, acknowledging the history of the market without exposing the league’s primary asset to the logistical risks of a sub-zero environment.

The Structural Failure of Soldier Field

A different set of constraints bars Chicago, the third-largest media market in the country. Soldier Field should theoretically be a prime contender given the city’s massive hotel stock and dual international airports. However, the stadium is blacklisted due to a capacity deficit resulting from its controversial 2003 renovation. The project, which cost upwards of $600 million, famously inserted a modern bowl into the historic colonnades but resulted in the smallest capacity in the NFL at approximately 61,500 seats. This shortfall of 8,500 seats compared to the 70,000-seat benchmark represents a potential loss of over $20 million in gate receipts alone for a single Super Bowl.

Furthermore, the city’s decision not to install a roof during the renovation left the venue exposed to Lake Michigan’s brutal winter winds, failing the climate mandate. Chicago Bears President Kevin Warren has explicitly linked the team’s desire for a new stadium in Arlington Heights to this failure, noting that a new domed facility is the only path to a Super Bowl bid by 2031. Until such a facility is constructed, Chicago remains the largest American market incapable of hosting the league’s premier event.

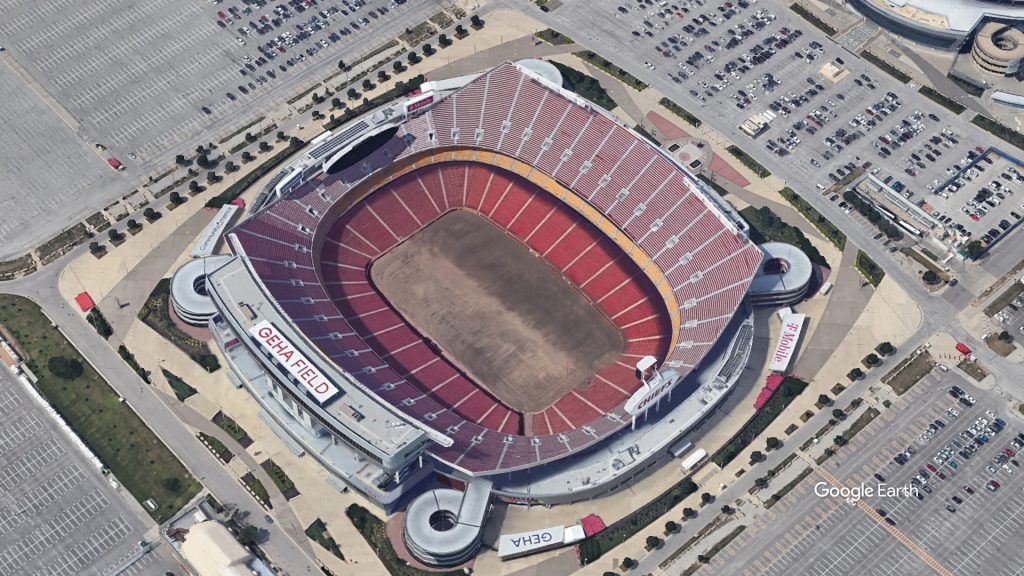

The Rolling Roof Debacle at Arrowhead

Perhaps the most tragic case of exclusion belongs to Kansas City’s Arrowhead Stadium, which actually secured a conditional bid to host Super Bowl XLIX. In 2005, NFL owners voted to award the game to Kansas City, contingent on the passage of a sales tax measure to fund the construction of a “rolling roof” that would slide between Arrowhead and the adjacent Kauffman Stadium. This structural innovation would have provided the necessary climate control to satisfy league requirements.

However, in April 2006, Jackson County voters rejected the $170 million roof proposal while approving other renovations. Consequently, Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt was forced to withdraw the bid, and the game was re-awarded to Arizona. Despite the Chiefs establishing a modern dynasty with Patrick Mahomes, the lack of a roof and the average February low temperature of 25 degrees Fahrenheit keeps one of the league’s loudest stadiums out of the rotation. The failure of the vote cemented the reality that on-field excellence does not override architectural deficiency in the eyes of the NFL’s selection committee.

Strategic Isolation in New England

In New England, the exclusion of Gillette Stadium was a deliberate strategic choice by ownership. When financing the stadium in 2002, owner Robert Kraft opted against a dome, explicitly stating that he did not want to lose the competitive advantage of cold-weather games. Kraft noted that opposing players dislike coming into the cold, a factor that undeniably aided the Patriots during their dynasty years. This decision, however, permanently alienated the venue from Super Bowl consideration, as Foxborough’s average February temperature of 39 degrees falls well below the league’s threshold.

Additionally, the stadium’s location on Route 1, equidistant from Boston and Providence, lacks the centralized urban campus required for the week-long fan festivals and media centers that accompany the modern Super Bowl. Without a centralized hub of high-end hotels and convention space within walking distance or a short shuttle ride, the logistical friction is viewed as too high for the league’s corporate partners.

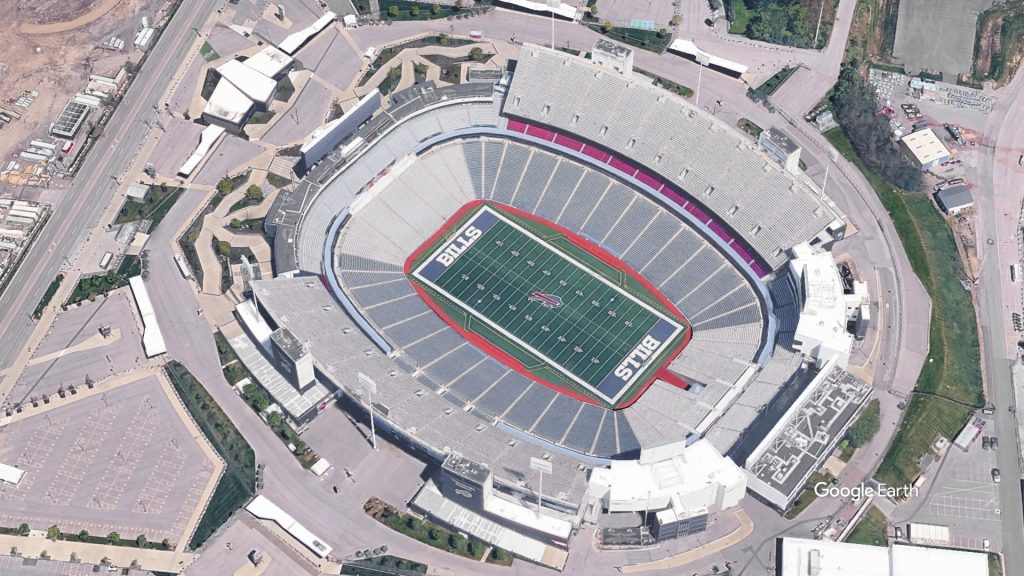

The Buffalo Stance and the New Highmark Stadium

The Buffalo Bills recently reaffirmed the divide between “football stadiums” and “Super Bowl stages” with their design for the new Highmark Stadium, set to open in 2026. Facing a choice between a $1.5 billion open-air venue or a significantly more expensive dome, the Pegula family and local officials chose the former. This decision was driven by the cultural identity of Buffalo football, which is inextricably linked to the elements, and the financial reality that a dome would not solve the region’s lack of 5-star hotel inventory.

By choosing an open-air design in a city prone to lake-effect snow bands that can paralyze travel, Buffalo effectively signed a contract acknowledging they would never host the championship game. Civic leaders admitted that the region lacked the infrastructure to host a Super Bowl regardless of the roof status, making the additional cost of a dome a poor investment. This acceptance highlights a growing bifurcation in stadium design between venues built for local fans and venues built for global events.

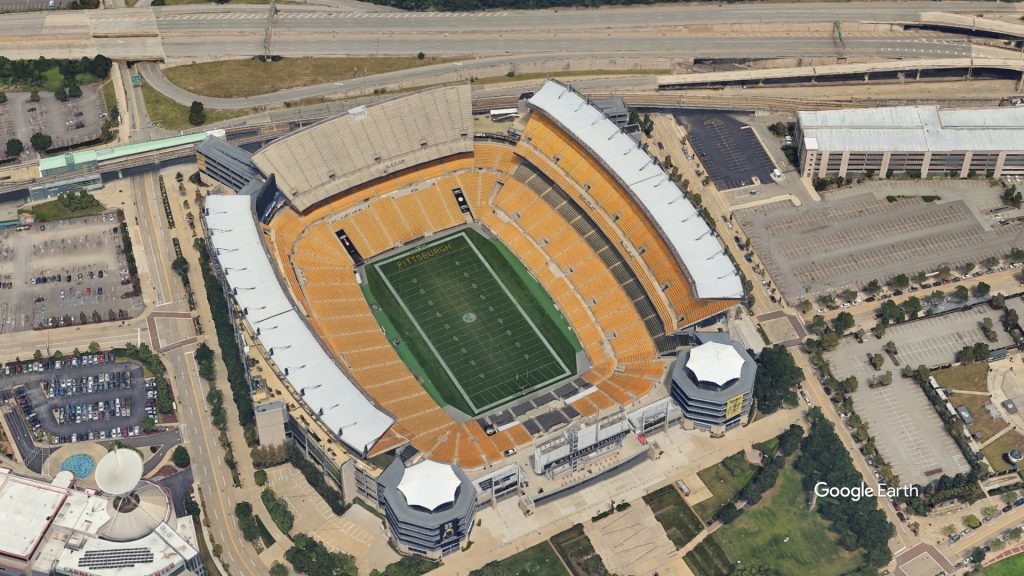

The Steel City’s Ceiling: Acrisure Stadium

Pittsburgh’s Acrisure Stadium, formerly Heinz Field, occupies a similar position of historical prestige stifled by modern logistical demands. While the Steelers ownership, the Rooney family, holds immense sway within the league, the venue fails to meet two legs of the infrastructure stool. First, the stadium’s capacity of 68,400 falls just short of the 70,000-seat preference, a deficit that reduces potential revenue. Second, and more critically, the city faces a significant hotel inventory shortage. Team President Art Rooney II has publicly acknowledged that the city needs “a couple more hotels” to be a viable contender, as the current high-end inventory is insufficient to house the NFL’s traveling circus.

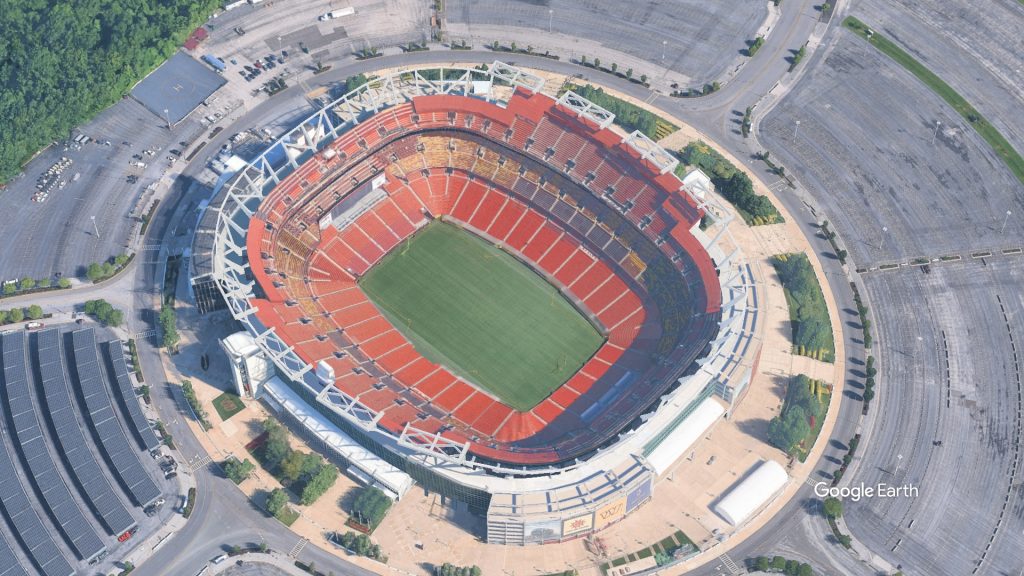

The Capital’s Crumbling Stage: Northwest Stadium

Just outside the nation’s capital, Northwest Stadium—known as FedEx Field until its renaming in August 2024—represents a different kind of exclusion. Despite serving the Washington Commanders in a top-tier media market since 1997, the venue has long been plagued by a reputation for aging infrastructure and a poor fan experience. While it once boasted the largest capacity in the NFL, its open-air design and location in Landover, Maryland, miles from the cultural hub of D.C., have kept it out of Super Bowl contention.

Recognizing that the current facility is structurally obsolete for hosting a modern Super Bowl, the franchise is aggressively pursuing a replacement. The team’s ownership group is actively planning a return to the site of the former RFK Stadium in the District of Columbia. Crucially, the proposed design for this new venue features a translucent dome. This architectural pivot serves as a direct admission that in the modern NFL, a roof is the price of admission for hosting the league’s championship game.

The Exception That Proved the Rule

The strict enforcement of these weather rules is reinforced by the memory of the league’s single deviation from them: Super Bowl XLVIII in New York/New Jersey. Awarded as a one-time “reward” to the Giants and Jets for privately financing MetLife Stadium, the event was marketed as a return to the game’s gritty roots. While the game time temperature was a manageable 49 degrees, a massive winter storm struck the region just hours after the festivities concluded.

League executives and owners viewed this near-miss as a warning; had the storm arrived twelve hours earlier, it would have caused a “transportation apocalypse” for the private jets and transit systems essential to the event’s logistics. This “doomsday scenario” effectively closed the door on future cold-weather experiments for cities like Philadelphia and Washington, reinforcing the necessity of the climate mandate.

The Two-Tiered Future of the League

Consequently, the NFL has bifurcated its stadiums into two distinct tiers: the “Event Hubs” and the “Football Fields.” The Event Hubs—Las Vegas, New Orleans, Los Angeles, Atlanta, and soon Nashville—feature climate-controlled domes and are located in major tourism centers capable of absorbing 150,000 visitors. Nashville’s upcoming enclosed stadium has already drawn praise from Commissioner Roger Goodell, who called the city “Super Bowl ready” now that they are building a proper “stage”.

Conversely, the historic open-air venues in Green Bay, Pittsburgh, and Kansas City will remain the sites of memorable playoff battles but will never host the final spectacle. The Super Bowl has ceased to be merely a football game played where the sport is rooted; it is now a television product requiring a controlled studio environment, leaving the frozen tundras of the sport’s history permanently on the outside looking in.